Organizing Content

Effective instructors are effective storytellers (Harrington & Zakrajsek, 2017). They organize content—often sequentially—in a way that delivers practical lessons or morals (see Building Learning Objectives); highlights important themes; and helps their audience make connections between individuals, events, actions, and concepts.

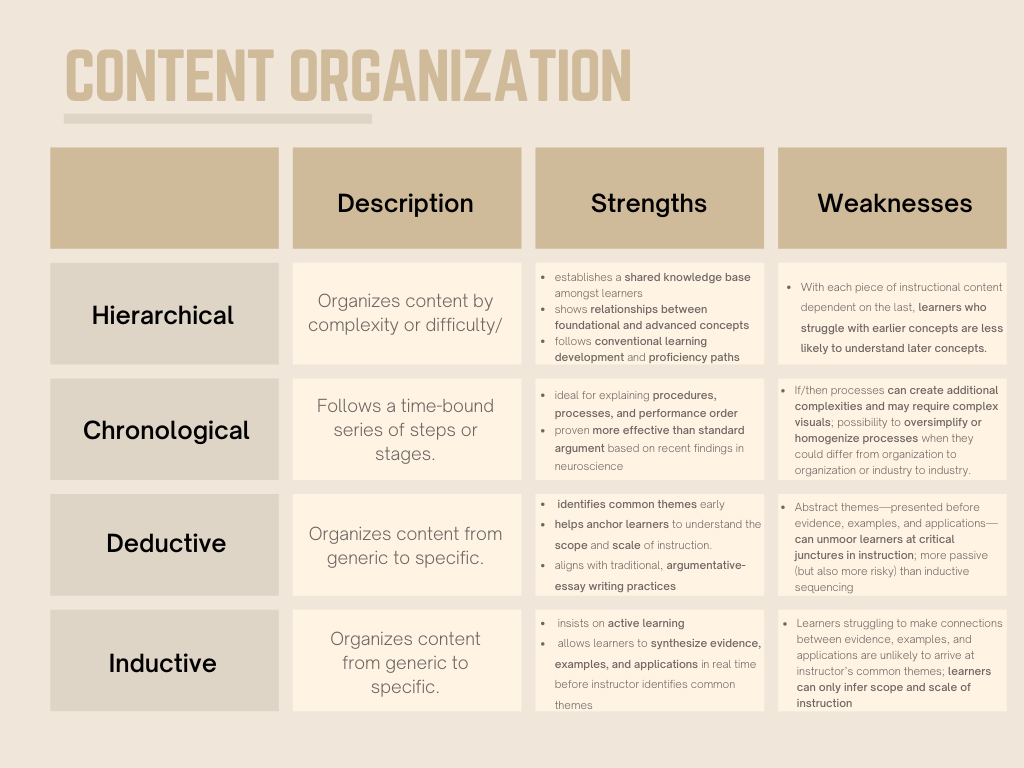

Below are common content-sequencing strategies that can help you become a better storyteller. It’s important to choose a delivery approach that works best for you as well as the type of story that you’re trying to tell.

Hierarchical: Organizes content by complexity or difficulty; establishes basic or easier-to-understand foundations with which to build more complex or harder-to-grasp concepts (which can, in turn become new foundations to build even more concepts, etc.)

Strengths: establishes a shared knowledge base amongst learners, illustrates relationships between foundational and advanced concepts, follows conventional learning development and proficiency paths (e.g., novice—> intermediate —> advanced —> expert)

Weaknesses: With each piece of instructional content dependent on the last, learners who struggle with earlier concepts are less likely to understand later concepts.

Example: Basics of insurance—> Basics of insurance policies —> Health insurance policies —> Medical expenses covered by health insurance policies

Chronological: Follows a time-bound series of steps or stages; aligns with traditional narrative practices, a beginning, middle, and end, and structured with an introduction, problem, steps to resolution, and conclusion.

Strengths: ideal for explaining procedures, processes, and performance order; proven more effective than standard argument based on recent findings in neuroscience (Vaccaro, Scott, Gimbel, & Kaplan, 2021).

Weaknesses: If/then processes can create additional complexities and may require complex visuals; possibility to oversimplify or homogenize processes when they could differ from organization to organization or industry to industry.

Example: Policyholder pays premium —> Policyholder suffers loss covered in policy —> Insurer covers financial loss

Deductive: Organizes content from generic to specific; establishes common themes and follows with supporting evidence, examples, and applications

Strengths: identifies common themes early, helping anchor learners understand the scope and scale of instruction; aligns with traditional, argumentative-essay writing practices

Weaknesses: Abstract themes—presented before evidence, examples, and applications—can unmoor learners at critical junctures in instruction; more passive (but also more risky) than inductive sequencing

Example: Insurance companies are a critical part of the economy —> Insurers help businesses make investments and take risks they might not otherwise be able to, increasing economic growth and innovation —> Insurers invest premiums, driving economic growth —> Insurers promote risk prevention strategies, better stabilizing the economy should a catastrophic even occur

Inductive: Organizes content from specific to generic; identifies evidence, examples, and applications that culminate with key themes

Strengths: insists on active learning, allowing learners to synthesize evidence, examples, and applications in real time before instructor identifies common themes

Weaknesses: Learners struggling to make connections between evidence, examples, and applications are unlikely to arrive at instructor’s common themes; learners can only infer scope and scale of instruction

Example: Insurers help businesses make investments and take risks they might not otherwise be able to, increasing economic growth and innovation —> Insurers invest premiums, driving economic growth —> Insurers promote risk prevention strategies, better stabilizing the economy should a catastrophic even occur —> Insurance companies are a critical part of the economy

References

Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus.

Vaccaro, A. G., Scott, B., Gimbel S. I., & Kaplan, J. T. (2021). Functional brain connectivity during narrative processing relates to transportation and story influence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.665319

Second Column for Figures, etc.